The Coleford, Monmouth,

Usk and Pontypool Railway

(The CMUPR)

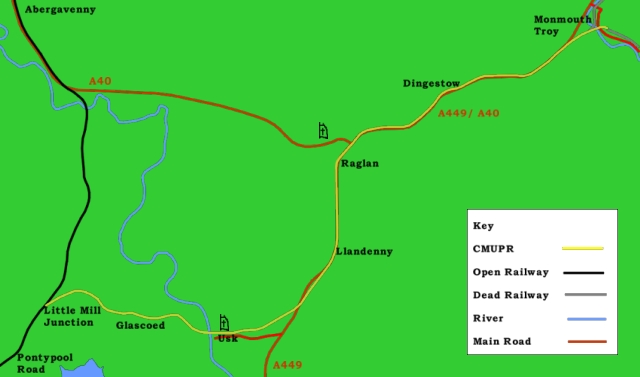

The CMUPR had the longest

history and the longest title of all the railways to Monmouth

(we apologise if the title doesn't fit on your screen). The first

stretch of its proposed route began to be used for transport

in 1810 with the opening of the Monmouth Tramroad between Coleford

and Monmouth; the trackbed between Usk and Monmouth is at the

busiest it has ever been in its new form as the A449/ A40 dual

carriageway.

The first serious plans came

very early on - in the 1840s - for a Dean Forest, Monmouth, Usk

and Pontypool Railway, which would have done an even worse job

at fitting on the screen. It was one of these lines that failed

fairly early on, although more of it was eventually built than

was usual for such railways; the largest single chunk and the

first bit to be opened was that taken on and proposed again by

the CMUPR in 1855. (The other end was built by the Forest of

Dean Central Railway with even less success and the bits in the

middle were bungled together from tramways, except for a proposed

tunnel under a hill in the middle of the Forest which was never

built at all.)

The actual railway was opened

from Pontypool to Usk in 1856 and reached Monmouth in 1857 after

a rather tricky construction featuring several financial problems

and a collapsing tunnel. None of the Monmouth railways had easy

births - three struggled financially before they even opened,

one was considerably overdue and obsolete by opening and the

fifth was stillborn - but the CMUPR should really have had it

easiest, given the largely flat or gently rolling terrain that

its route passed through between Pontypool and Monmouth. The

terminus, at Monmouth Troy, was built on the outskirts of the

town with the aim of converting it to a through station for trains

to Coleford. The decision was farsighted and showed the great

plans that the Company had for its railway.

When you see a modern road

and think that it doesn't seem to have been built for the traffic

levels that it's carrying, that's partly because the Governments

of the 1950s and 1960s learnt from the railways and didn't pour

money down holes that they could make much smaller. Monmouth

Troy became a through station, but it never obtained the importance

planned for it and its atrocious location, well away from the

centre of Monmouth, could be held partially responsible for the

loss of Monmouth's rail services in 1959. By then the CMUPR was

already dead; the last regular through train to Monmouth had

run in 1955. The Company managed to extend across the Wye to

Wyesham in 1861 (with considerable outside support); it survived

in theory to see the completion of the extension to Coleford

over the Monmouth Tramroad in 1883 four years before it was officially

absorbed into the Great Western, which had held a lease on the

line since 1863 and had run trains over it from the outset. This

somewhat delayed completion of the Company's scheme was little

more than winding branch line which, isolated from the main rail

networks in the Forest of Dean, disappeared in 1917. The CMUPR,

uniquely amongst Monmouth's railways, was built for the subsequent

provision of double line (both tunnels and most bridges were

wide enough) but the second track was never laid.

A closure proposal in 1954

was rejected and replaced with a remarkable service increase

from four trains each way each day to eleven. Six months isn't

really long enough for a new service to bed in (although the

response was still a remarkable increase in traffic), losses

continued and the line closed in the middle of a national rail

strike the following year. In 1960 the line between Usk and Monmouth

was removed and today just a stub remains at the Pontypool end

to serve a Royal Ordnance Factory. This was a rather security-conscious

starting point and the line was somewhat out of the way and insignificant,

so pictures of this stub don't seem to be exceptionally common.

A couple of photos from 1989 in The Ross, Monmouth and Pontypool

Road Line show a train that is so anonymous (unnamed blue

Class 47 diesel loco, unbranded Speedlink van, rake of 1950s

four-wheeled vans, equally anonymous 1980s four-wheeled van)

that it is suspiciously so and obviously carrying something which

is trying too hard not to be noticed.

Monmouth's first railway is

also its last; like the Wye Valley line, nowadays the Coleford,

Monmouth, Usk and Pontypool Railway's stub is derelict and overgrown.

It lasted to the age of 137 and the mainline connection - uniquely

for the four - remains in place.

The presence of the dual carriageway

on much of the route is in many respects a compliment - the railway

has been approved for use into the 21st century and passed for

70mph running. Sadly it is no longer a railway however, and reopening

throughout is unlikely. Usk could be reunited with the rail network

for the cost of 1½ miles of track - all but one of the

bridges along the route are still in place, the station platforms

at Usk are intact and the site is vacant. The junction is fully

signalled (unlike that at Wye Valley Junction, which was set

up as a siding). A link to Monmouth would involve realigning

bits of the dual carriageway (particularly between Usk and Llandenny)

and modifying a couple of junctions, which would allow the railway

to run along the western side of the road through Raglan and

Dingestow stations. At Monmouth a new tunnel could be bored to

carry the railway to a new Riverside station just yards from

the town centre or the road could be extensively rebuilt to allow

the railway to pass under it and head into Troy station. Alternatively

the line could be allowed to pass under the new road at the former

Cefn Tilla Halt and run up the east side of the road, free to

swing away on the approach to Monmouth Tunnel and somehow working

around the sliproads on the road junction at Raglan. Unfortunately

all these options would cost huge sums of money and for that

reason it will never happen.

Meanwhile Troy's main station

building survives at Winchcombe station on the Gloucestershire

and Warwickshire Railway, Dingestow station is a private residence

and Raglan is part of a road maintenance depot. There are proposals

to move Raglan station building to the Museum of Welsh Life at

St Fagans - the Museum has a large gap in its collection, with

a complete absence of mass-transport related artifacts to cover

the contribution that railways and canals made to Welsh life.

The entire line between Monmouth and Pontypool is currently regarded

as being in Wales and a complete plan of the railway can be found

in the National Library of Wales at Aberystwyth, although the

rolling landscape is hardly typical of the Principality. Unfortunately

the six fine pine trees which used to stand over the Raglan station

cannot go with it - five were felled to make way for the A449,

although the survivor will probably survive the removal of the

building. The only remaining building along the entire line will

then be the station building at Dingestow.

Despite through trains between

Ross and Pontypool ceasing after the two lines came under one

owner in 1923, the route is still counted as one line for the

purposes of maintaining the few surviving structures and is accordingly

catalogued as "ROS". Mileages are counted from Ross

on Wye. What the management of the senior railway would think

of this is unrecorded.

|

Pontypool Road

|

Pontypool Road opened in 1854;

it was then a fairly insignificant station on the Newport, Abergavenny

and Hereford Railway. The following year it became a junction

when Pontypool got a decent station in the town centre with the

opening of the Taff Vale Extension line to Crumlin Junction in

the Ebbw Valley a few miles to the west. The year after that

it became the junction for Usk via the railway that is the subject

of this article. That was extended to Monmouth the next year.

Within another year the Taff Vale Extension had been extended

to the Taff Vale and made a junction with the Taff Vale Railway

at Quakers Yard. (The neighbouring Rhymney Railway had been planning

to use this extension too, but it took so long to be completed

that they got bored and built another line.)

Two lines to nearby Blaenavon

followed. The lower line was run by the Great Western Railway

and terminated at Blaenavon Low Level. The upper line was run

by the London and North Western Railway and ran through Blaenavon

High Level, over the highest point on the standard gauge rail

network in England and Wales at Waenavon and down the mountainside

to join the Newport, Abergavenny and Hereford just south of Abergavenny

station. The Pontypool, Caerleon and Newport Railway opened in

1874 and provided a second connection from here to the docks

at Newport.

Pontypool Road thus got to

be a major junction. It was rebuilt in 1908 to feature one great

island platform with bays at each end (the south one serving

various branches and the north one exclusively for Monmouth trains).

Signals arrayed themselves impressively around the station area.

A massive loco shed, rakes of carriage sidings and masses of

marshalling yards around the station and the triangular junction

to the south of the station to the south completed the scene.

The two lines to Newport began

to be rationalised in the 19th century before the network had

quite reached its peak. Passenger services through Blaenavon

High Level were suspended "for the duration" (of the

Second World War) in 1941 and never resumed. The north bay lost

all traffic in 1955 when Monmouth services ceased. Then in 1962

Blaenavon Low Level closed, along with the older line to Newport.

The Taff Vale Extension went in 1964; a collapsing viaduct beyond

Quaker's Yard (opened in 1864) probably helped the case for the

closure of the only one of Pontypool's branches to be condemned

by Beeching. The station was cut back - literally. Apart from

the loss of the bay platforms, buildings, canopy and most of

its services, the core platform was also sliced back at each

end. Its former extent is particularly obvious in the upper picture;

much of the area of grass between the two main running lines

used to be platform.

The remaining colliery traffic

from the London and North Western route ceased shortly after

the Miners' Strike in the 1980s. All claims to junction status

were finally swept away when the first branch to be completed

became the last to completely go in 1993. Only one signal remains

in the entire station site - signal LM104, visible with its back

to the camera in the upper picture. It is controlled by the signal

box at Little Mill. It is a very stark contrast to "Pontypool

Roads" "out on the mainline" featured in Ivor

the Engine - although Ivor himself can still be seen occasionally

on the Pontypool and Blaenavon Railway, which has preserved a

particularly steeply-graded section of track heading north for

a couple of miles from Blaenavon High Level.

The lower picture shows one

of the Class 175 "Coriada" units which now operate

services over the Newport, Abergavenny and Hereford and provide

Pontypool and New Inn, as the station is now known, with one

train in each direction every two hours. Northbound trains tend

to head either to Manchester or to Holyhead; southbound ones

variously terminate at Cardiff Central, Carmarthen or Milford

Haven.

Trains for the Monmouth branch

would head north from their bay platform - there were no regular

passenger trains from starting points beyond Pontypool Road and

branch passengers would have to book another ticket at the junction

if they wanted to go further afield - and run up the mainline

for about a mile to the junction at Little Mill. Unlike Pontypool

Road, Little Mill has lost little of its old importance - partly

because it never had any importance. |

|

East of Little Mill Junction

|

Little Mill Junction does

not actually feature in this picture. It is one of those annoying

junctions which isn't near any handy overbridges, passed by a

footpath or sat by a station, so you have to either engage in

a spot of trespassing or take pictures out of train windows.

The former is a trifle dangerous and results in images which

we can't show you; the latter is a bit expensive for the quality

of the image which can be obtained but will have to be used for

Little Mill at a suitable moment.

The junction had a junction

station, but it was really only for branch trains. The result

was a reasonable service for the little village connecting them

to Pontypool and Usk from a little wayside platform with a decent

building. It was the most impressive of the four junctions at

the non-Monmouth end of the Monmouth branchlines, with a set

of sidings and a tidy array of signals.

After the line closed to passenger

trains the station was demolished, but the access road remains

with no warning at the outer end that it leads exclusively to

railway property (although it is tidily padlocked occasionally).

Little Mill signal box remains and the junction has survived

intact, complete with signalling and a modern 10mph speed restriction

board. Trains can no longer run to Glascoed whenever they

like, however, since some cad has put a bufferstop across the

line a chain or so from the 15mph speed limit board which allows

trains to accelerate to that daredevil speed for their journey

along Monmouth's last railway.

Branch Lines to Monmouth cites the 31st of January 1993 as

the last freight train over the branch. The track is now overgrown.

The ominous warning sign, seen here at a foot crossing on the

south-western outskirts of Little Mill, seems a little amusing

upon looking up and seeing the rails behind. A board at a crossing

further up demands that you "Stop, Look, Listen" on

a line clearly not used in many years when you want to use an

equally derelict track over the railway. |

|

Glascoed

|

Glascoed is a very small and

quiet village a mile from the railway, but nonetheless once boasted

three stations. However, only one of these - sited on the other

side of this bridge - was intended to serve the local population;

the other two were provided for the benefit of the workers at

the nearby Glascoed Royal Ordnance Factory. They were a little

further up the line - the diminuitive Glascoed Factory West Access

Halt was quarter of a mile up the line, while Glascoed Factory

East Access Halt was three quarters of a mile beyond that.

Glascoed Halt, located just

to the east of a fine stone overbridge with a brick arch, was

a little timber trestle platform with a standard GWR "pagoda"

shelter which opened in 1927. It was on the right-hand side of

the single running line which passed under the left-hand side

of the bridge. When a loop was laid for the factory it was moved

to the left-hand side of the running line - such are the benefits

of kit-built stations. Books on the line all agree that it was

27¾ miles from Ross on Wye. This is unfortunate, because

this is the only bridge in the area which qualifies but the milepost

on the other side proclaims that it is 27½ miles from

Ross on Wye. It is, of course, quite possible that when the new

milepost was being made up (it is a modern metal milepost rather

than an old wooden one) someone forgot how to count to three.

Equally, the books could be wrong. The bridge is rather unobliging

and does not carry an engineer's code announcing how far from

Ross it is. Since the matter is of little importance we won't

bother to cast a vote on it.

The entire CMUPR was originally

set out for double track but only a single line was laid. Like

most other railways in the country which were set up this way

the railway remained single track for its entire career. However,

it did have the benefit that a loop line for the Royal Ordnance

Factory could be provided without having to widen the bridge.

Glascoed thus became one of the very few halts in the country

with full signalling and a signal box. The three halts all closed

when the passenger service was axed and the signal box went with

the section from here to Usk. However, unlike the Wye Valley

line, the bridges all seem to be in reasonable condition. |

|

Usk and Usk Tunnel

|

Usk station was the initial

terminus of the line, opening on the 2nd of June 1856 pending

the completion of the line to Monmouth. It and Monmouth Troy

would ultimately both be laid out in a very similar manner, with

a double track line running into a tunnel (inside which the double

line reduced to single), the goods yard and main buildings both

to the right of the tunnel and a river crossing at the opposite

end of the station to the tunnel. The fact that both had many

detailed differences - for example, the bridge here was over

the Usk and carried double track while at Monmouth there were

two single track bridges over the Wye - merely shows what variations

can be made to an unoriginal theme.

The extension to Monmouth

met many little difficulties, the principal of which was the

tunnel at the east end of Usk station (west portal in the middle

picture, inside in the bottom picture). It notably fell in during

proceedings, resuling in some rather interesting internal profile

variations. (Other tunnels on the Monmouth rail network have

little oddities - Lydbrook, on the Ross and Monmouth, has two

styles of lining, while Tidenham, on the Wye Valley line, has

lengthy unlined sections - but none of the other nine have mis-matching

portals and wobbles in the lining.) However, the line was successfully

completed and subsequently opened on the 12th October 1857.

The station was lightly described

by one J. H. Clarke in 1891 as a "miserable little hut"

which had been opened with the line and seen minimal improvement

since. Progress was made and in 1897 a new set of facilities

were completed to provide passengers with greater comfort. Edwardian

views of the station show a very tidy site with handsome structures,

a covered footbridge to link the two platforms and the station

name written in creepers trained to climb appropriately up the

cliff to the left of the tunnel portal.

Decline then duly set in.

The station's resemblance to its younger sibling at Monmouth

began to vanish with the loss of the footbridge in the Second

World War. Trees grew up and hid the rockface, though a drop

in staffing levels meant that there was less time to train the

creepers anyway. Business slackened slightly in the inter-war

years. All passenger trains and through goods services to Monmouth

ceased on the 28th of May 1955 when driver's union ASLEF held

a national strike; formal closure came on the 13th of June, the

day before the strike was settled and services on all other lines

in the country were able to resume (not quite as normal, however

- the pay rise demanded was obtained at the expense of the long-term

future of the network when the country used the two-week cessation

of services to realise that it could largely manage quite happily

without railways).

The line to Monmouth was then

used for wagon storage - a fate to which several abandoned lines

succumbed while British Railways worked out how many wagons they

had actually inherited at Nationalisation. (They had also inherited

the official documentation on how many wagons they should have

inherited, but said documentation turned out to be slightly less

reliable than tea leaves.) On the 12th of October 1957 a final

passenger train celebrated the line's 100th birthday by running

to Monmouth and back. The track through the main platform (left

in the top picture, right in the middle) was lifted in 1959 and

swiftly followed by the line from here to Monmouth. The remains

of the station closed on the 13th of September 1965. Subsequently

the line was cut back to Glascoed; a bridge on the west bank

of the Usk over the A472 Pontypool to Usk road was removed soon

after and the continuity of the trackbed broken.

Yet 45 years on this bridge

remains the only point on the line from Little Mill to Usk where

the continuity of the trackbed has been broken. Re-instating

the bridge would now be more acceptable (it would impose a height

limit on passing lorries, but there's one of those at the Little

Mill end of the road too so it wouldn't prevent its use as a

through route). Passenger trains funding the upkeep of the line

would encourage BAe Systems to start using it again. Usk station

is largely ready for the return of trains with its still-intact

platforms (see upper picture). The double-track infrastructure

would allow a half-hourly service to and from Newport or Cardiff

with a footpath remaining over the river bridge.

Why not? |

|

East of Usk

|

Once out of Usk Tunnel the

line ran through a cutting along the north flank of Usk before

heading out on a slight embankment into open country (railways

are very bad at deigning to run at the same level as the surrounding

land). The open country duly carried it around to Cefn Tilla

Halt, where the line picked up the Olway Brook (which was straightened

to make life easier) and followed its valley up to Raglan.

The trackbed is seriously

broken for the first time in this area. This picture looks roughly

eastwards along the line towards the end of a linear nature reserve

now developed along the old cutting. The heavily overgrown bridge

allows a suburban road to cross on a skewed route. Beyond is

a short length of cutting which has been partially infilled to

allow a new suburban road to be run across the line. After that

the trackbed disappears into the general landscape for a bit,

although it doesn't appear to have been seriously built over.

Should the line be reopened

to Usk it would be worth giving serious consideration to making

this the eastern terminus, rather than Usk station. It would

serve a few hundred additional people and allow a Park and Ride

station conveniently situated for the A449, which has a junction

about a mile away. The trees to the left would make it feel like

a real Great Western station. On the downside, half of the attractive

and secluded nature reserve would get turned into a railway and

it would become a substantially narrower green avenue. |

|

Cefn Tilla Halt

|

Cefn Tilla Halt was the last

new station to open on the Monmouth rail network. The 1954 timetable

change brought an additional 7 trains each way each day between

Pontypool and Monmouth and accompanied this by slowing services

slightly with a nice new halt at Cefn Tilla. This had the benefit

that the express locomotive named after the Court of the same

name could now stop at the local station - although the line

was not noted for the frequent visits by express locomotives

and the cab of your average Great Western express loco was larger

than the halt platform.

Cefn Tilla was the ultimate

display of low-cost service improvements (nobody asked at this

point if unremunative services were really best improved by providing

additional isolated stops however). The platform was located

in a slight cutting just north of a minor road overbridge a mile

out of Usk adjacent to an attractive stone cottage; the six-foot

long wooden structure, with the nameboard on the cutting wall

behind it, was sat on the half of the cutting set aside for the

never-laid southbound track. It did not last long enough to appear

on maps, though it is reported to have managed around ten passengers

a day (which meant that during the peak timetable it got one

passenger for every two trains). Closure came less than a year

after it opened.

Nowadays the insignificant

halt is well up in the "Disappearing stations" rankings.

The slight embankments on each side of the cutting were swept

away after closure. Bridge, halt and house all vanished under

four lanes of tarmac with the opening of the A449 dual carriageway

between Newport and Monmouth. A slight gap in the trees in the

centre of the image marks where the railway once headed northwards

from the little halt. |

|

Llandenny

|

Llandenny station was the

smallest of the four intermediate stations on the branch; it

had no platform shelter and fairly minimal facilities. Curiously

it was also, of the three stations between Usk and Monmouth,

the closest to the village that it intended to serve, which was

only a few yards away.

The station was split across

a level crossing, with the station buildings, platform and signal

box on the south side of the crossing (about where the van is

in this view) and the loop and cattle dock on the north side.

A couple of sidings branched off to the right and lay behind

the main station building.

The only real changes over

the station's entire existence were that after closure the grass

got a bit longer, the buildings and crossing gates got a little

more dilapidated and the nameboard and seat vanished. Otherwise

it was a largely unchanging station in the shadow of some gently

growing pine trees in an attractive rural spot.

It is rather less attractive

and rural now. Llandenny is less of a place for the curious to

get off the train and nose around too. Instead, traffic swoops

past at 70mph. A "Spot the Difference" competition

between this view and pictures of the active station (though

it never was a real centre of activity) resulted in the eventual

verdict that the background hills look more or less the same.

The local road now has a bridge rather than a level crossing. |

|

Raglan Road Crossing Halt

|

The original station at Raglan

was, for some obscure reason, two miles from a village which

the railway passed within half a mile of - probably something

about the main road in the area crossing the line here, thus

saving them the bother of building a road to link the railway

and making the railhead for the area accessible to lots of people.

It is also about equidistant between Dingestow and Usk, allowing

that section of line to be broken neatly in half and thereby

maximising the capacity of the single line. The reason as to

why the inhabitants of the largest centre of population should

have to walk two miles to their station was so obvious that the

traincrew were unable to persuade the passengers of the indisputable

and entirely logical reasoning behind locating the station as

far away from any habitation as it is possible to get in this

area and took to depositing passengers at the platformless Raglan

Footpath instead. Subsequently (in a largely unprecedented and

almost never-to-be-repeated move) the railway company realised

that it had put its station in the wrong place and built a new

one at Raglan.

The original site completely

fell into disuse and was largely ignored by trains for some years,

but when the GWR decided to slow down trains on this line a bit

by adding a few extra stops re-opening the original Raglan station

was fairly high on the agenda and services to the new halt began

on the 24th of November 1930. This was a railway with a long

name, so appropriately Raglan Road Crossing Halt seemed to be

named with the intention of competing with Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch

in the "stupidly long name stakes".

The halt, with its little

dirt-and-timber platform, did a fairly good job of serving the

local community (which can be seen to the left of the picture)

over its career. It had a small corrogated steel shelter of the

type used on the Wye Valley line. After closure it soon became

overgrown; both it and the level crossing were swept away for

the dual carriageway built on the alignment in the 1970s. |

|

Raglan

|

Raglan was the last station

on the line to open (although a few halts would come later).

Trains stopped here from very early on due to the fairly convenient

location of the point in relation to a footpath to the village

with its rather fine, if not particularly medieval, ruined castle.

After the Great Western took over the line in 1863 steps began

to be taken - rather slowly - to upgrade the route and Raglan

Footpath was relaunched as Raglan station in 1876.

Like all the other stations

on the line, goods facilities were provided at one end of the

station site (the north end on this occasion) rather than opposite

the platform. The platform instead overlooked a rather fine row

of six pine trees. On this platform was a fairly handsome, if

slightly basic, brick building with a simple awning. It was not

in character with any of the other stations along the line.

The station was still not

exactly in Raglan - the walk is not unattractive but is equally

not likely to encourage traffic. The poor location of the station

in relation to the second largest intermediate centre of population

(after Usk) won't have helped business. Nonetheless, the dead

station has done rather well in terms of simple survival. Unlike

Llandenny, the building escaped demolition to make way for the

A449 and still stands today on one side of a road maintenence

centre alongside the dual carriageway, which is out of view to

the left. One tree also remains. A prefabricated goods shed which

once stood in the goods yard is apparently now at Norchard on

the Dean Forest Railway. |

|

Elms Bridge

|

Elms Bridge was the last of

the three halts opened on the line by the Great Western, leaving

Cefn Tilla to be opened under British Railways. The little dirt

and timber platform was located just north of a high stone bridge

at the bottom of the deep cutting used by the railway to pass

into the Trothy Valley for the remainder of the journey to Monmouth

(in which direction this picture was taken). It was on the left-hand

side of the line and accessed by a steep path. The nearest named

centres of population are Coed-y-fedw (on the left hand side

of the road three-quarters of a mile away) and Pen-y-clawdd (about

a mile away right), both of which are fairly minor, although

the latter does warrant a church with a tower. Unfortunately

they are linked by the next bridge on the line towards Monmouth,

which did not get a halt; Elms Bridge Halt was on the road that

linked a small hamlet a few hundred yards up a hill to the left

with Kingcoed, two miles to the south and already served by Raglan

Road Crossing Halt. One feels that whoever decided where trains

on the CMUPR should stop had some very strange ideas as to the

best way to select stopping locations.

When your station is named

after the adjacent farmhouse ("The Elms" - the actual

trees have probably been dead since the 1970s) it is not exactly

setting out for a great career. (Other surrounding farms include

Twyn-yr-argoed and The Warrage.) However, it did manage 22 years

before closure, after which the photographers turned up and made

it look really unsuccessful by photographing its grass-grown

shelter-free platform. The cutting was dramatically widened for

the A449 (augmented by the A40 north of Raglan) and the road

bridge replaced by one which is twice as wide as it needs to

be. Were it not for the road, it would be very easy to picture

exactly how rural these stations once were. |

|

Dingestow

|

Dingestow station holds the

record for being the most intact of the CMUPR stations, since

it retains its building, station master's house and platform,

which all survive in a station footprint which is completely

intact. It is evidently well-looked after with someone still

living in the station house; consequently obtaining a decent

photo really requires their permission to wander around the place

and they seemed to be out on both occasions when we called, so

a photo over the gate had to suffice.

The brick building most closely

resembles Llandenny and bears little resemblance to the buildings

at Usk, Raglan and Monmouth Troy, which were built during the

20-year-long upgrade of the line. It is therefore more likely

that it is original; if so, it is probably the only CMUPR building

in decent condition.

The village is an attractive

place and produced an average of over 15 passengers per day in

peak years. Levels of business then slowly slipped (to about

6 passengers per day) and staffing levels were reduced by two-thirds

(to 1) by the 1930s. After closure the site slowly became overgrown,

but seems to have been doing well enough by the time the road

came along to justify the planners showing a spot of imagination

and finding the road its own course for a few yards to pass the

station behind the line of trees. It is not as quiet as it used

to be, but its future seems assured. |

|

Monmouth Troy

|

Monmouth Troy station, situated

in the shadow of the Gibralter Rock, marked the end of the line

for the first four years but was always intended as a through

station. Trains arrived from Usk through a short tunnel and immediately

entered the two-platform station, with the crossover into the

Usk-bound platform being situated in the tunnel. The platforms

ran in a straight line away from the camera; the goods yard was

off to the left. Its facilities were initially fairly basic,

but as its importance rose the station was developed and its

building tally increased.

An extension to Wyesham came

in 1861 - a short extension, but nonetheless expensive. The Monnow

Valley Railway began work on another tunnel off to the left in

1865, which would have carried it under the north flank of the

Gibralter Rock, around the south flank of Monmouth and up the

Monnow Valley to Pontrilas. This scheme collapsed, leaving a

short isolated tunnel which would have required new platforms

on another alignment across the goods yard were it to carry passengers.

The Ross and Monmouth Railway arrived in 1874 and was worked

with the line from Pontypool as a through route until 1923. The

Wye Valley Railway came from Chepstow in 1876; it was due to

provide a turntable for the station to allow tender engines to

frequent the lines, but that fell through. Expansion finished

with the completion of the Coleford extension by the GWR in 1883.

After the Coleford Branch

closed in 1917 the station settled down as a country junction

at the centre of three independently worked branchlines. Each

supplied four daily passenger trains and a daily freight train.

Passenger services peaked in 1954 with 19 arrivals each day.

This then dropped back to 12 for the first half of 1955, slumped

to 8 after the closure of the CMUPR and collapsed to one daily

freight (Sundays excepted) from Chepstow between 1959 and 1964.

Looking down from above the

tunnel portal now it is hard to believe the bustle that could

once have centred on the station at peak times. It was used as

a lorry base and coal distribution centre for about two decades

after closure. The footbridge between the two platforms was removed

in July 1957; the buffet and the shelter on the second platform

were removed after total closure in 1964. The main building was

removed to Winchcombe station on the Gloucestershire & Warwickshire

Railway in 1986. The goods shed was demolished in 2001. The goods

yard is now a housing estate, but the platform area, linking

the bridges at the west end with the blocked-up tunnel portal

at the east, remains clear. The station is still the epitome

of the rural country station - quiet, attractively sited and

closed, though perchance not forever. |

|

Wyesham Wharf

|

Wyesham Wharf was at the eastern

end of the 1862 extension of the line, most of which was located

on a highly expensive viaduct. The wharf was a standard transhippment

wharf with the tramway from Coleford to Monmouth May Hill up

on the platform and the CMUPR providing a few sidings alongside.

When the Wye Valley Railway

arrived in 1876 it created an end-on junction with the older

railway and the line over the viaduct was given the necessary

overhaul to allow it to carry passenger trains. The wharf fell

into disuse and disappeared when the Coleford Branch was built. Thus

in 1883 the site became a proper junction, although the actual

junction proper was at the far end of the layout.

The WVR passed into Great

Western control in 1905, bringing all rails at the junction under

a common owner. Junction status was lost when the Coleford Branch

closed in 1917, but some importance was regained when a halt

was built behind the camera in 1931. Passenger services ceased

in 1959, with snowballs being thrown at the final special train

on the 4th of January; the last train was a goods working from

Monmouth Troy five years and two days later.

Now Wyesham holds the record

of being the only place on the WVR to build significantly on

its railway past; the trackbed runs between the fence on the

left and the thin strip of rough ground towards the right to

vanish under the houses in the distance. Happily there is plenty

of room around the back for a new formation to veer around the

obstruction. |

Reopening possibilities are

dealt with above; for some reason a spur to Usk has never been

considered at the same length as Wye Valley regeneration. The

disappearance of much of the trackbed and the lack of a suitable

inspiration point (the refurbished Tintern station probably has

a lot to answer for) will be factors in this. Reinstating the

line to Usk also doesn't have the same "big bang" quality

as a large-scale expensive link overcoming the odds to run trains

through Tidenham Tunnel again either. Usk would undoubtably benefit

from the link and it would put Raglan within a reasonable

walking distance of the rail network (and within a comfortable

cycling distance), showing the ability of short rail spurs to

pierce potential tourist areas and widen the area accessible

to those from further afield without a car.

But if the WVR is deemed to

be little-known then that almost leaves no category to put this

railway in. Which may be why the main page for this part of the

website is headed with "The Wye Valley Railway" rather

than "The Coleford, Monmouth, Usk and Pontypool Railway".

That and the fact that the latter is just too long-winded to

head an internationally-read webpage. "The Trothy Valley

Railway" would have been so much snappier; sadly the very

briefly proposed cut-off from Abergavenny to Raglan, which would

have followed the Trothy for a little longer, was never built.

|

The background image on this

page shows the line from the overbridge on the east side of Usk,

looking back down the nature reserve towards Usk Tunnel and the

former station. |

More information and "past"

photos can be found in Branch

Lines to Monmouth (Vic Mitchell and Keith Smith, Middleton

Press, 2008) and The Ross, Monmouth and Pontypool Road Line

(Stanley C. Jenkins, Oakwood Press, 2002, 2009). The

National Archives hold the GWR survey of the line under RAIL

274/56

<<<Wye

Valley Railway<<<

>>>Forest

of Dean Central Railway>>>

>>>Ross

and Monmouth Railway>>>

>>>Coleford

Branch>>>

<<<Railways

Department<<< |